Krystal’s Story

Krystal was standing before the judge in housing court when her water broke.

Several months earlier, her landlord sent her a letter asking her to move out, after she had called the City to request an inspection. Krystal knew this wrong, and tried to keep paying her rent on time, but he refused to take it from her. He then filed for eviction, when she was seven-months pregnant. Having an eviction on her record, Krystal knew, would make it impossible for her to find another apartment. “He was not only trying to keep me from moving out, but he was also trying to prevent me from moving forward,” she thought.

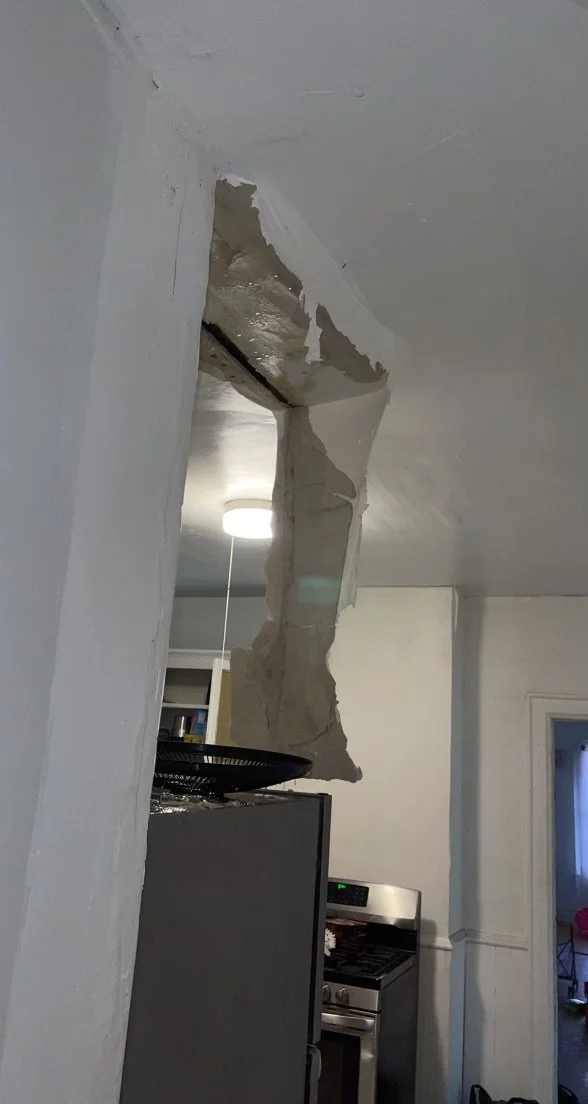

Krystal tried repeatedly to get him to take her payments, once even as he fled in his van, despite the condition of her home. Mold sprouted on the walls when it rained, and her children were getting sick. The ceiling in her bedroom had collapsed, leaving a gaping hole—so Krystal had moved her bed to the living room and set a bin under the leak. When the drain backed up, as it often did, water flooded the entire basement, once filling it with feces. A city inspector came once and told her that it sure looked like she had lead paint—but he never tested anything, and never came back to check up. When her landlord heard, he tried chipping off the paint himself—right next to the kids’ breakfast table.

On top of that, it was, Krystal explained, “just this eyesore.” The front door no longer worked, because the knob had fallen off and the landlord refused to replace it. “He just said, No, it's too expensive. I'm not going to change it,“ Krystal explained. The windows were cracked; some were painted shut, while others wouldn’t lock. Empty brackets lacked smoke detectors, and the ceiling fans didn’t work. The one working heater would blow out when the basement flooded. And for all this, Krystal paid $1200 a month in rent—when her landlord wasn’t running away from her.

An eviction on her record would make it incredibly difficult to attain a new apartment. “It really makes you look bad. It makes you look bad in general,” Krystal explained. And she wasn’t going to let that happen. She taught herself tenant law, and made sure that she got back to court once she had delivered her baby. The court agreed that she should not have an eviction on her record, and now she is excited to be planning for a move to a new apartment. “I’m trying to be as prepared as I can be,” she says, for her family’s next chapter.

Tanzil’s Story

Tanzil’s rental had never really been great. “It looked like nobody lived in there for a while,” she remembers thinking, but she told herself she could make it into something nice. It had a yard, at least, which she thought would be great for her young daughter. And she could just afford the $750 a month rent.

But the problems started right away. The first sign was in the bathroom. A pipe started dripping onto the floor—Tanzil wondered where that water came from—then leaks developed over the shower. The ceiling leak over the toilet rusted it out, and though there was nowhere to sit, the landlord refused to fix it. “One time,” she recalled, “I had to go to the bathroom in a bowl.”

Next to collapse was the kitchen roof, and along with the water came roaches. Lots of roaches. Once when Tanzil woke up in the night, “the floor was covered with roaches. Like they were everywhere. It was like if you was sticking your hand in a jar of roaches.” The upstairs tenant had them too. “When they would go to sleep the roaches would be on her and her kids, and her kids would just smack it off and be like, ‘It's okay; it's just a roach.’” Tanzil started sleeping in her truck with her daughter.

Finally a city inspector came, but nothing changed: “He was like, ‘This house is condemned. It's not livable.” But all he could do was write a citation; Tanzil needed somewhere to live. She had tried crashing with friends, staying in a motel, living in the car—and finally checked herself and her daughter into a shelter. For nine months, working over 50 hours a week, she lived with her daughter in a halfway house, sharing quarters with a shifting array of roommates. “I just felt like at one point, I was in a room and all four walls was just slowly closing on me,” she recalled. “And I didn't know what to do. Because like that mental state--I see how people, even though it's not right, choose to end their life”

Finally, she has an apartment she loves, though, and she notes that for the first time in her life she has not moved for two entire years. Tanzil is going back to school and studying accounting now. “I don't want to be taken advantage of as a woman,” she says. “I feel like I got to play catch up to be where I want to be in life, but I can't look at everybody else’s past; I’ve got to stay focused on mine, because greater things are coming.”

Dora’s story

Dora has had to be resourceful. The apartment came with no refrigerator and no stove, but “I make it work with my air fryer and my little hotplate,” she says. A sheet wadded up by the doorjamb keeps out the snow, and the window is wedged shut with a sponge, to keep out the dust from the trains that pass all day. The mousetraps don’t work for the mice, she says, so “I'm using [them] for the roaches because they're really dumb. They just go right in.”

Some problems, though, workarounds can’t fix. The smoke detectors go off at random times, the shower is forever clogging, and the basement floods. When she asked for the mousehole in the kitchen to be addressed, the rental manager just stuck a wire scrubber in the hole—and now the mouse nudges it back out each day. Mostly, however, the complaints aren’t resolved. “You put the work order in,” she says, “and it takes . . . whenever they get to you.”

“I want to be able to be feel safe where I live,” says Dora. “I’ve had times where I couldn't even come in with my groceries, because the whole street was locked up because somebody was shooting.” Shootings are not uncommon in the neighborhood, and the police don’t seem to do much, so “nobody really sees nobody, nobody really comes outside. Nobody really goes anywhere here,” she explains. She worries because her son is Black and Hispanic: “It's not the safest when you live in a neighborhood like this . . . I’d rather just move away and make sure he's in a safe neighborhood than run a risk of getting killed or getting into drugs or gangs.” But what makes Dora most nervous is the empty apartment next door. It’s not secured, and has become a target for vandalism and a hangout for bored young people. “There’s a lot of kids, all ages. And those are the same kids that can’t play in the playground, so they go into empty houses and do stuff they shouldn't be doing, and nobody does anything about it.”

As a little kid in Puerto Rico, she says, “I used to be able to run around, ride my bike, skate…” Now, she’d just like somewhere safe and clean, so her son could go outside: “You know, where my kid is able to have this play area. I just want a place where he can run.”

Karl’s and Keith’s Stories

Karl is in the process of moving out of an apartment building that is in terrible shape. He pays over $800, and the landlord wants to raise the rent $50. When they moved in, though, it was nice. “It wasn’t like this,” Keith explains. “It was really nice.” Then the owner’s sons took over, and now it’s owned by a shifting array of LLCs.

Karl and his father both worry that the apartment is actually bad for their health. They don’t trust the contractors who have come in to “fix” the building, and who leave building materials all over the hallways and stairs. An exterminator came in with no protective equipment, no identification, and wouldn’t hand over information about what he was spraying. Fire extinguishers are missing, and the smoke alarms aren’t properly installed. And then there’s the mold that continually sprouts on the living room walls. It gets painted over, but keeps reappearing.

After they complained, the building inspector came—but not for over a month. He was shocked by the conditions, said Keith, and he admitted that the city’s inspections department is many years behind. They issued many citations, including for the dangerous basement-- because the ceiling is only held up by jacks. In response, management just put a lock on the basement door, even though tenants still had possessions in storage. That closed off the laundry room, but they had been cited there as well, for having no carbon monoxide detector. Still, Karl and Keith can see the basement, right through the hole in the bedroom floor.

The biggest problem are the doors that open up onto . . . nothing. On each floor is a doorway—with no lock, no real closure even—and when you open the door, there’s just a drop. Ten feet, twenty feet, or more: they’re scary to even look out. For the folks with little kids, Karl and Keith figure, it must be terrifying.

Karl’s excited about the new place, especially the kitchen. “One day,” he says, he would love to own “something with land, so I could grow my own products.” In the meantime, he just wants to make sure he can get his family somewhere safe.